One of my favorite scifi/fantasy novels to return to, Claw of Conc remains a headspinner. The only cliched action sequences are dealt with and dismissed early on, in order to confirm how insignificant they are to the real story. I always feel a wince when I realize the biggest battle Severian engages in is with cave dwelling pale apes in an obviously false mission to save his quite dead love from the first book. It’s almost a slap on the wrist to the reader to remind themselves where they actually are.

And where are we? In the autobiography of an as yet unconfirmed resident of the House Absolute, sometime in the future. Our not too hero-ish protagonist Severian wanders the country of Urth, reacting blindly, eking out an existence as an executioner when he remembers to, while being thrown all manner of allusive hints as to where and who he may be. There’s a true perversion of the Last Supper, that complicates the narrator’s identity immensely, a riff on the question game from Rosencrantz and Gildenstern, whole plays acted out, then transcripted (for those not paying attention), a mythic quest battle that only takes place in a book Severian/Thecla/Other reads when they are bored (ponder that one!), and before the dismissive ending that simply repeats ShadowTorturer’s, another king-murdering reference when a small coven of witches (and others) shows up plotting in ruins. There’s a king/queen in yellow, and some giant undersea interstellar monsters for the Lovecraft fans, too.

Before you think these are just name-dropping allusions, know that they are also informed explorations of transubstantiation’s political significance, Meno’s knowledge (again), the allusive device itself, and a reinvention of the ‘bookend’. Dizzy yet?

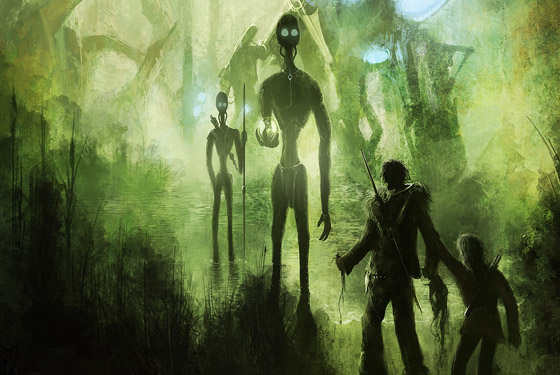

If not, ‘Urth’-shattering details are also dropped so casually you find yourself turning back again and again to make sure you’ve got the context correct. Identity becomes both subject-of , and clue-for what is happening behind and around the narrative. The floating giant bodies of the Abaia, the needle mouthed faces of the cacogens, the illusive appearances of ‘The Autarch’ themselves, the saddest android ever, Jonas, and the political machinations of Vodalus that may include Severian’s earliest ‘memories’. All these vex you, as often as the masterful language dazzles.

Wolfe philosophizes on the nature of desire, on vanity, on dreams, on identity, change, history, progress, revolution, and most of all storytelling itself.

in a novel callled The Claw of The Conciliator, the so-named device is sucessfully employed less than half the time, is kept in a boot, and whenever mentioned, all agree it should simply be returned to its owners. It’s owners? The Perelines, who burned down the church they worshipped it in when it was stolen, because hey, it was no longer there. In that footnote alone, the perversion of logic, faith and ethics into new puzzle, is what Wolfe’s Book of The New Sun is all about.

Wolfe, Gene (1994-10-15). Sword & Citadel: The Second Half of 'The Book of the New Sun': The Second Half of the Book of the New Sun (Kindle Locations 6811-6819). Tom Doherty Associates. Kindle Edition.

Wolfe, Gene (1994-10-15). Sword & Citadel: The Second Half of 'The Book of the New Sun': The Second Half of the Book of the New Sun (Kindle Locations 6811-6819). Tom Doherty Associates. Kindle Edition.